Birth date: March 5th, 1941

Hometown: Mio, Mihama-cho, Hidaka, Wakayama

Filming date: November 10th, 2019

The location of filming: Former Mio elementary school

Contents

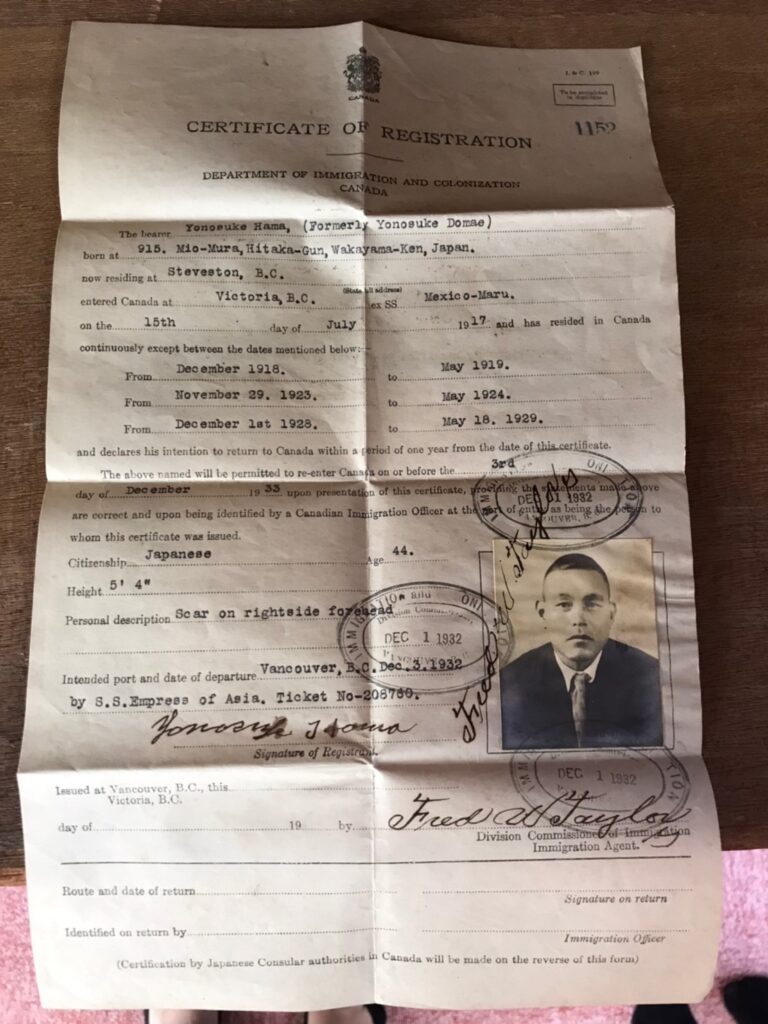

Harumi Hirao was born and raised in Mio, Wakayama, talks about her family who had emigrated to Canada. Her grandfather, Yonosuke Hama, had emigrated to Steveston for the first time in 1917. Her uncles, Seitaro and Shigeo, also emigrated to Canada when they were 18 years old. In this video, she talks about memories with Yonosuke and how he spent his time in Mio when he returned to Japan around 1932. Harumi's story also highlights some of the Canadian customs and lifestyles that returnees had adapted into their daily life in Mio with cultural practices such as table manners.

People emigrated to Canada

・Yonosuke Hama (Harumi’s grandfather)

・Seitaro Hama (Harumi’s father’s brother)

・Shigeo Hama (Seitaro’s younger brother)

Harumi said she had never met Seitaro, but had seen Shigeo on three different occasions. Both Yonosuke and Seitaro worked in fishing when they emigrated to Canada. Shigeo worked in the forestry industry and worked in a sawmill.

Relationship with Nikkei

When Dr. Lisa Domae, a Nikkei sansei, came to Mio in March 2019 to trace the origin of her family, we found that her father Stan Sadao Domae was a cousin to Tadao Hama, who is Harumi’s father. Lisa and Harumi didn’t know each other until then, but thanks to this discovery, Mr. Sadao and Harumi was able to meet online on August 29th, 2020.

Yonosuke Hama’s certificate of registration

Yonosuke’s original family name was “Domae”, and he and Toyokichi, who was Stan Sadao Domae’s grandfather, were siblings.

Source: photo provided by Harumi Hirao

Fishing in Steveston and the relationship between Nikkei and First Nations

In 1920, there were about 100 canneries in Steveston which is located the mouth of the Fraser River in British Columbia.(3) At that time, cannery employees had various racial and ethnic backgrounds including Europeans, Japanese, Chinese and First Nations.(3) Also, the division of works was established in the canneries, for example, Japanese were in charge of salmon fishing and Chinese were in charge of canning and First Nations worked as assistants.(3) On the other hand, at the canneries in the north of BC, few Chinese were employed.(3) Instead, whites handled most of the main work, and Japanese and First Nations handled fishing and canning.(3) As you can see, the system of the division of labor was different depending on each community.(3) In addition, according to Harumi, at the cannery where Yonosuke and Seitaro used to work, a man called Mr. Tanaka, who was born in Mio, was a boss who lent boats and equipment to fishermen, and most Nikkei had engaged in fishing under him.

The website about the cannery in Steveston (English ver.): "Steveston Cannery Row" by Patricia Jordan

According to the article “THE SOYOKAZE: A Gentle Wind That Weathered the Storm”, Shigekazu Matsunaga was born in Canada in 1908 and brought up in Mio, Japan. When he moved to Quathiaski Cove, Canada where his uncle lived and worked, the Quathiaski cannery was a multiracial community. At the cannery, 5 Nikkei families engaged in fishing along with skilled Chinese and native Canadians.(4)

The video that focused on the vessel “SOYOKAZE” that the Matsunaga family from Mio used at that time: The Soyokaze Story

In the interview, Harumi told that Yonosuke brought back clothes such as socks and cowichan sweater with him when he came back to Mio, Japan. From this fact, the works was separated per races but where they worked was same, so it can be thought that Nikkei had a cultural relationship with the natives and other races. Actually, Nikkei fishermen who engaged in fishing in the beginning of migration had relationship between the natives and other races at the cannery.

【References】

(1) 足立照也(Teruya Adachi)(2016).「北西太平洋岸先住民社会における先住民ツーリズムに関する研究ノート」(「Hokuseitaiheiyogishisenjuminshakai-ni-okeru-senjumintsurizumu-ni-kansuru-kenkyunoto」),『阪南論集社会科学編』(『Hannanronshu-shakaikagakuhen』), 51(3), P.105-P.122

(2) 山田公二(Kinji Yamada)(2020). 「世界の子ども事情 カナダ・先住民文化剥奪の標的となった子どもたち」(「Sekai-no-kodomojijo Kanada ・Senjumimbunkahakudatsu-no-hyotekitonatta-kodomotachi」),『はらっぱ』(『Harappa』), NO394, P.42-P43

(3) 河原典史(Norifumi Kawahara) (2017). 「戦前のカナダに渡り漁業に従事した日本人」(「Senzen-no-kanada-ni-watari-gyogyo-ni-jujishita-nihonjin」),『RADIANT 立命館大学研究活動報』(『RADIANT Ritsumeikandaigakukenkyukatsudoho』), http://www.ritsumei.ac.jp/research/radiant/gastronomy/story7.html/, (Saishuetsurambi 2020.10/31)

(4) Beth Boyce (2020). “THE SOYOKAZE: A Gentle Wind That Weathered the Storm”, BC STUDIES, NO204, P.183

(5) カナダ移住百年誌編集委員会(kanadaijuhyakunenshi-henshuiinkai) (1989). 『カナダ移住百年誌』(『Kanadaijuhyakunenshi』), 美浜町カナダ移住100周年記念事業実行委員会(Mihamacho-kanadaiju-100shunen-kinenjigyo-jikkoiinkai), P.117-P.135

(6) 山田千香子(Chikako Yamada) (2000). 『カナダ日系社会の文化変容「海を渡った日本の村」三世代の変遷』(『Kanadanikkeishakai-no-bunkahenyo「Umi-wo-watatta-nihon-no-mura」Sansedai-no-hensen』), 御茶の水書房(Ochanomizushobo), P.109-P.121

(7) 「カナダインディアンの文化」(「Kanadaindeian-no-bunka」),『CANADIAN SPRIT GALERRY』, https://firstnations.jp/page/culture/. (Saishuetsurambi 2020.10/30)

(8) (2015). 「ファースト・ネーションズ (先住民族インディアン)」(「Fuasutoneshonzu (Senjuminzoku-indeian)」),『Government of Canada』, https://www.canadainternational.gc.ca/japan-japon/about-a_propos/faq-first_nations-indien.aspx?lang=jpn , (Saishuetsurambi 2020.10/30)

(9) 小山茂春(Shigeharu Koyama) (1984). 「第4章 三尾移民の歩んだ道」(「Dai4sho -Mioimin-no-ayunda-michi」), 『わがルーツ・アメリカ村 老人たちはいま』(『Wagarutsu・amerikamura Rojintachihaima』) , ミネルヴァ書房(Minerubuashobo), P.126-P.148

(10) 田中裕介(Yusuke Tanaka) (2009). 「先住民と日系カナダ人」(「Senjumin-to-nikkeikanadajin」), 『立命館産業社会論集』(『Ritsumeikansangyoshakaironshu』), dai45kan dai2go, P.92-P.93